Source photos: nanaironohouseki.tumblr.

skip to main |

skip to sidebar

170202 4CC CM 2種 por YzRIKO

“It’s the true era of quads.”

– Yuzuru’s words in the video, translated by yuzusorbet.tumblr.

(Will be cheering for you at 4CC. Yuzu,ganbatte!! Praying for you to be healthy and strong in all ways.)

FOUR CONTINENTS CHAMPIONSHIPS 2017

LOCATION: South Korea

SCHEDULE OF EVENTS

Date /Time/ Event

Tuesday, February 14 / All day / Official Practice

Tuesday, February 14 / 10:00 / PAIRS - Technical Panel Meeting

Tuesday, February 14 / 11:00 / Team Leaders Meeting

Tuesday, February 14 / 12:15 ICE DANCE - Technical Panel Meeting

Tuesday, February 14 / 18:10 LADIES - Technical Panel Meeting

Wednesday, February 15 / All day / Official Practice

Wednesday, February 15 / 08:30 / Referee & Technical Controllers Meeting

Wednesday, February 15 / 09:30 / ICE DANCE - Initial Judges Meeting

Wednesday, February 15 / 11:30 / PAIRS - Initial Judges Meeting

Wednesday, February 15 / 12:10 / MEN - Technical Panel Meeting

Wednesday, February 15 / 17:00 / LADIES - Initial Judges Meeting

Wednesday, February 15/ 20:00 / ISU and Judges Dinner

Thursday, February 16/ 09:00 / MEN - Initial Judges Meeting

Thursday, February 16 / /11:00 / ICE DANCE - Short Dance

Thursday, February 16 / 14:15 / PAIRS - Short Program

Thursday, February 16 / 17:00 / Opening Ceremony on Ice

Thursday, February 16 / 17:50 / LADIES - Short Program

Friday, February 17 / 13:30 / ICE DANCE - Free Dance

Friday, February 17 / 17:45 / MEN - Short Program

Friday, February 17 / 18:00 / ICE DANCE – Technical Panel Review Meeting

Saturday, February 18 / 09:00 / ICE DANCE – Judges Round Table Discussion

Saturday, February 18 / 14:00 / PAIRS – Free Skating

Saturday, February 18 / 18:00 / LADIES – Free Skating

Saturday, February 18 / 18:15 / PAIRS – Technical Panel Review Meeting

Sunday, February 19 / 07:00 / PAIRS – Judges Round Table Discussion

Sunday, February 19 / 07:45 / LADIES – Technical Panel Review Meeting

Sunday, February 19 / 09:00 / LADIES – Judges Round Table Discussion

Sunday, February 19 / 11:00 / MEN – Free Skating

Sunday, February 19 / 16:30 / MEN – Technical Panel Review Meeting

Sunday, February 19 / 17:30 / EXHIBITION

Sunday, February 19 / 17:45 / MEN - Judges Round Table Discussion

Sunday, February 19 / 21:00 Closing Banquet

Please note: This schedule is subject to change.

By Akiko Tamura

Source: ifsmagazine

The competitive figure skating spirit that we see today in Japan is the result of a carefully planned and well-executed program that was set in place more than two decades ago.

Many wonder how it has become such a strong nation in recent years, producing one champion after another. There is no one simple answer, but the result is a combination of various factors that have contributed to that nation’s rise on the global stages.

Figure skating has a long history in Japan dating back to the late 1920s in the men’s field and the mid-1930s in the ladies’ discipline.

The Japanese Skating Federation (JSF) was founded in 1929. Kazuyoshi Oimatsu, the federation’s first Olympic representative, placed ninth at the 1932 Olympic Winter Games in Lake Placid, N.Y.

Etsuko Inada, who won seven national titles, was the first lady to represent Japan at the Winter Games. In 1936, at age 12, she placed 10th in of a field of 23.

One of the first skaters to represent Japan in the modern era was Nobuo Satō, who dominated the sport domestically for a decade, winning 10 consecutive national titles from 1957 to 1966. It is a record that has not been broken to this day.

Satō’s fourth-place finish at the 1965 World Championships marked Japan’s highest result at the global competition. He was invited to go on tour with the medalists, but had to leave before it completed its run to compete at the national championships. “When I was competing it was a different era,” Satō recalled.

“That was a time everyone believed that if you are a student, school has to come first. So Japanese nationals were held during the spring break in March.”

Satō, the father of 1994 World champion Yuka Sato and the current coach of Mao Asada, retired following a fifth-place finish at 1966 Worlds and turned to coaching. Kumiko Okawa, his first student, placed fifth at the 1967 and 1968 World Championships. Satō later married Okawa, who is also a well-respected coach in her own right.

Tsuguhiko Kozuka, a three-time national champion, and his son, Takahiko Kozuka, the 2011 World silver medalist, were both coached by Satō.

Minoru Sano captured the first World medal, a bronze, at the first World Championships that Japan hosted in Tokyo in 1977. Shoichiro Tsuzuki, one of Yuzuru Hanyu’s first coaches, was Sano’s main coach; Satō worked with him on compulsory figures. “We had three strong men at the time: Sano, Fumio Igarashi (a two-time NHK Trophy champion and fourth at 1981 Worlds), and Mitsuru Matsumura (sixth at the 1980 World Championships),” Satō recalled. “The three of them challenged each other and the rivalry helped all of them to become better skaters. Rivalry was always the key.”

Emi Watanabe was the first lady to medal at a World Championships, capturing the bronze in 1979. Born to a Filipino mother and Japanese father, Watanabe was fluent in both Japanese and English. Her coach, Etsuko Inada, recommended that she to go to the U.S. to train, a move that was considered highly unusual at the time. At age 10, Watanabe relocated to the U.S. to work with Felix Kaspar, and later with Carlo Fassi.

Unlike today, it was rare in that era for Japanese skaters to train abroad, due to the language barrier and the financial considerations. Those factors made Watanabe’s successful path a hard act to follow. Watanabe became Japan’s sweetheart following those World Championships and “Emi” was the most popular first name for baby girls born that year. Then came Midori Ito, who completely revolutionized ladies figure skating in Japan.

CHANGING PERSPECTIVE

Machiko Yamada, who competed in the 1960s, recalled how different figure skating was during her era than it is today. “I did not enjoy skating because my coaches were very strict and I was afraid of them. That was the generation — everyone was pretty much like that at the time.”

Yamada could not wait to quit competing and when she did, she turned to coaching. Decades later Yamada, now 73, still works out of the same rink in Nagoya where she coached Ito to international glory so many years ago. Looking back on her own career, Yamada said she realized that if she had enjoyed skating more, she probably would have done better. “When I started coaching, it wasn’t like I had a big ambition, but I decided that I would make sure my students enjoyed skating.”

She remembers the day she first spotted a tiny 5-year-old Ito skating tirelessly around the rink. “It wasn’t like, ‘Wow, she has talent!’” Yamada recalled. “I noticed her because she was enjoying skating so much — she never wanted to stop.”

Shortly after joining Yamada’s class, Ito’s talent became apparent to everyone. Ito mastered four different triple jumps while she was still in elementary school. Yamada said she was fearless as a child. When Ito’s parents separated and her family situation became complicated, she began spending more time at Yamada’s home, moving in permanently at age 10. Yamada said her initial goal was for Ito to be able to financially support herself in the future through her skating.

Yamada ended up guiding Ito to so much more than that initial objective, taking her to nine national titles, the 1989 World crown and Olympic silver in 1992.

Before Ito, Tokyo had been the center of the skating universe in Japan and those who trained outside the capital had to prove that they could skate. Ito’s success put Nagoya on the national figure skating map. At the time, the JSF was constantly looking for role models outside of Japan, a practice with which Yamada did not agree. “Back then, we always looked up to the top Western skaters and tried to copy them,” Yamada recalled. “But I felt that as long as we were copying somebody, we would never become number one.”

Ito then started working on the triple Axel, a jump no woman had ever landed, and at the 1988 NHK Trophy she cleanly executed the first triple Axel in international competition. The following year, Ito became the first Asian to ever win a World title. The little girl from Nagoya had become a global skating sensation.

Though she was the favorite heading into the 1992 Winter Olympic Games in Albertville, Ito ultimately placed second behind America’s Kristi Yamaguchi. But Ito’s personal story and her Olympic success ignited a new generation of girls to take up figure skating and the sport started to gain popularity in Japan.

A NATION ON THE RISE

Without doubt, Ito was the catalyst for the generations that followed, and it was through her that the JSF gained a lot of valuable knowledge. “We learned that having just one talented skater was not good enough. We needed to build a strong team,” said Noriko Shirota, then the assistant director of JSF. (In 1994, she became the JSF director, a position she held for 12 years).

In 1992, Shirota and the JSF staff established a Youth Development Summer Camp, with the initial objective of finding and developing young talent to prepare for the 1998 Olympic Winter Games in Nagano. In the first year, about 100 skaters between the ages 8 and 12 were selected from all parts of Japan to attend the camp.

While they were being tested for their skating abilities, the youngsters had the opportunity to meet their rivals and witness first-hand what others were capable of, with the hope that this would help cultivate their competitive spirit.

The JSF then began sending novice skaters to international competitions so that they could gain experience from an early age. That program continues today and has become an important foundation for building a continuous roster of talented young skaters.

While one generation is competing at the elite level on the international stages, the next is being groomed. Fumie Suguri, Daisuke Takahashi, Miki Ando, Mao Asada and Yuzuru Hanyu were among those who were discovered at the development camps over the ensuing years.

One of the biggest discoveries at the inaugural camp was Shizuka Arakawa. Six years later, the then 16-year-old represented Japan at the 1998 Games, where she finished 13th overall. “When I competed in Nagano, I didn’t fully understand the meaning of being at the Olympics. I just thought I was lucky,” Arakawa recalled.

In 2004, she won the World title in Dortmund, Germany. Everyone was surprised, including Arakawa. “I thought that if I skated clean, I may have a chance for a medal, but I never thought of winning the gold,” she said. “My goal was to show the best performance before I retired, and I thought it was a nice finale to my competitive skating career.”

Though she was ready to move on, those around her were questioning her timing. The next Olympics were two seasons away so why quit now, they asked. Over time, Arakawa rethought her earlier decision, adjusted her plan and began to focus on the 2006 Olympic goal. “In Nagano, I was happy just to be there, but I decided that if I was to go to Torino, I’m there to compete,” she recalled.

The investment by the JSF started to pay off during the 2003-2004 season when the Japanese ladies swept the elite international podiums. Miki Ando won the World Junior and Junior Grand Prix Final titles; Fumie Suguri claimed gold at the senior Grand Prix Final; Arakawa won the World title and Yukina Ohta captured the Four Continents crown.

Things did not go quite as well the following season, but the seeds had been sewn and a new sense of rivalry had developed. The ladies team for the 2006 Olympic Winter Games was selected after a fierce national battle between Suguri, Arakawa, Ando, Yoshie Onda and Yukari Nakano. Asada placed second at those nationals but was ineligible to compete at the upcoming Games due to her age.

Three ladies were selected: Ando, 18, was the only lady to have landed a quadruple jump (a Salchow); Suguri, 25, was a two-time World bronze medalist, and Arakawa, 23, the 2004 World champion. Each one had a reasonable chance to win a medal, so none of them had to bear the pressure alone.

In the end, it was Arakawa who skated into history when she won the 2006 Olympic title, the first athlete from Asia to ever mine Olympic gold in the sport of figure skating. It was the only medal Japan won at those Games.

She became an overnight superstar, and 14 years after the Ito era, Arakawa’s victory created yet another huge wave of figure skating fever. Shirota said the difference between Albertville and Torino was that Japan had made the investment to develop a team that was highly competitive. As she had said after the Games in Albertville, Japan needed to build a strong team and it had successfully done so, especially in the ladies’ discipline. Osamu Kato, the official trainer for JSF, remembered watching Ando and Asada at the Youth Development Summer Camp years earlier.

“Their exceptional physical abilities were so apparent,” he said. “Especially Mao, who had spring like nobody else — even on the floor she was hopping and skipping when everyone else was just walking.”

Asada’s talent was closely monitored from the outset. An admirer of Ito, Asada had landed a triple Axel-double toe loop combination at a local competition when she was 13. While still in sixth grade, she was invited to compete at Japanese nationals, where she landed a triple flip-triple loop-triple toe loop combination.

“I wish I could have preserved her in a time capsule,” Shirota lamented.

Yamada, who was Asada’s coach at that time, deflects any credit for her student’s jumping abilities. “I know people say I’m a good jump coach, but it was totally by accident that good jumpers came to me,” said Yamada, who also trained Onda and Nakano, both of whom were considered solid jumpers. “Personally, I always preferred expressive skaters. When I saw the Asada sisters I was thrilled and thought that they could be all-round skaters.”

Asada left Yamada after six years and relocated to the U.S. to train with Rafael Arutyunyan. She subsequently moved to work with Russia’s Tatiana Tarasova in the lead-up to the 2010 Olympic Winter Games.

The first Japanese skater to win three World titles, Asada found success at any early age and her continued rise on the international stages over the following decade spawned more waves of figure skating enthusiasm in Japan.

Asada’s triple Axel legacy has flowed down to the next generation. At the Junior Grand Prix event in Slovenia this September, 13-year-old Rika Kihira successfully landed a triple Axel on her way to winning the competition, defeating her teammate and current World Junior champion Marin Honda.

“Rivalry seems to be always the key to reaching the next level,” Satō said.

THE MEN STEP UP

Unlike the ladies, there was a long pause between Sano’s accomplishment at the World Championships and the next Japanese man to become an international star. Takeshi Honda, who at age 14 became the youngest man to ever win the national title, went on to claim two consecutive World bronze medals in 2002 and 2003.

When Honda retired in 2006, another star was waiting in the wings. Daisuke Takahashi found success at age 15 when he claimed Japan’s first World junior title in 2002.

Though he struggled in subsequent years to reach the podiums at senior competitions, it all came together one night on Olympic ice in Vancouver in 2010. There, Takahashi wrote his own piece of history when he claimed bronze, and became the first Japanese man to medal at an Olympic Winter Games in figure skating. A month later he won the World title, another first not just for Japan, but also for Asia.

“I always envied that it was the ladies that got all the attention. I was hoping to bring some of the spotlight onto the men as well,” Takahashi said.

His achievements marked a turning point for men’s figure skating in Japan. Just as he had hoped, more attention was focused on the male skaters. Fans started attending competitions in droves and the media began to take the sport seriously.

Nobunari Oda, another big star to come out of Japan, won the 2005 World Junior Championships, and in his senior debut later that year, claimed medals at both of his Grand Prix assignments.

Kozuka was the next member to join the club following his victory at the 2006 World Junior Championships. When he joined Takahashi and Oda in the senior ranks the following season, Japan had a trio of men vying for the top spot at the national championships. This three-way rivalry raised the bar domestically and turned nationals into a heated affair. All three captured the title at one time or another during a seven-year period.

The competition became especially fierce when a young man from Sendai joined the battle in the fall of 2010. Hanyu, the 2009 Junior Grand Prix Final and 2010 World Junior champion, adored Takahashi, but that did not stop him from claiming the national crown in 2012. Hanyu successfully defended his title the following season and entered the 2014 Olympic Winter Games as the reigning national champion and Japan’s best hope for a medal in Sochi.

To everyone’s surprise, Hanyu waltzed off with the gold medal, becoming the first Asian man to win an Olympic figure skating title. He has, in his few short years on the international circuit, set the bar technically and made history repeatedly. He holds the record for the highest score ever awarded under the current judging system, which he earned at the 2015 Grand Prix Final. Although his score of 330.43 seems untouchable — at least for now — Hanyu shows no sign of slowing down.

He opened the 2016-2017 season with another historical feat, successfully landing the first ratified quad loop at the Skate Canada Autumn Classic in Montreal in September. “I achieved what I achieved last season. It is natural for me to move forward and try something new,” said Hanyu, 21.

Shoma Uno, his 18-year-old homeland rival, successfully executed a quad flip at the Team Challenge Cup last April. He is the only skater to have landed this jump in competition to date.

Japanese figure skating has come a long way since Sano won Japan’s first World medal almost 40 years ago. In the past decade, Japanese skaters have claimed seven World titles and 12 other medals of varying colors; two Olympic crowns, as well as two silvers and a bronze, and have won five World Junior titles.

Every nation has its highs and lows, but the development of the Japanese skating program has seen it rise from being a nation of hit and miss wins to one of the strongest in the world.

Behind the scenes, there is a wealth of talent coming up through the ranks, and the nation seems virtually guaranteed to continue the success it has enjoyed throughout the past 15 years.

Originally published in the November/December 2016 issue of International Figure Skating magazine.

A tradução desse artigo para o português está aqui.

This blog is a summary of some facts of life and skater Yuzuru Hanyu career. The idea came from not find almost anything here in Brazil about Yuzuru and / or skating , but when searching the world discovered so things became difficult absorb and organize all ; hence this blog was born .

terça-feira, 14 de fevereiro de 2017

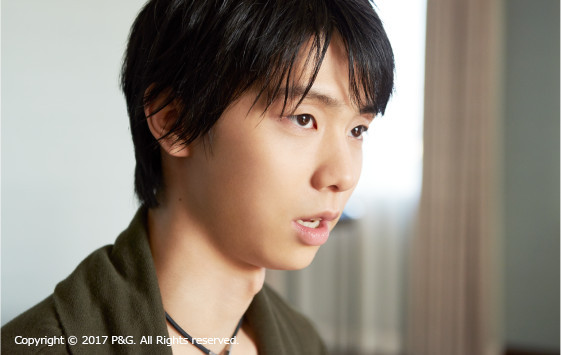

Yuzuru Hanyu in Lotte’s Ghana 2017 Valentine’s Day campaign.

Marcadores:

2017,

Campanha,

Lotte Ghana,

Yuzuru Hanyu

quinta-feira, 9 de fevereiro de 2017

Four Continents Championships; opening on 16th (Feb).- Video

170202 4CC CM 2種 por YzRIKO

“It’s the true era of quads.”

– Yuzuru’s words in the video, translated by yuzusorbet.tumblr.

(Will be cheering for you at 4CC. Yuzu,ganbatte!! Praying for you to be healthy and strong in all ways.)

Marcadores:

2016,

Patinação,

Videos,

Yuzuru Hanyu

YUZU DAYS, 6 Feb 2017.

–The reason for evolution, “the strength to aim for”–

Last season, Hanyu scored above 300 points in consecutive wins at NHK Trophy and GPF, and his GPF score was registered in the Guinness World Records. This season, he makes further evolution with the 1st successful quad loop in history and challenging 4 types of quads [t/n. should be 4 quads and 3 types] in his free programme. With a 4th straight GPF win which was a first in history, he prepares for World Championships coming up in March [t/n. and also 4CC coming in mid-Feb]. To Hanyu who continues to evolve, what kind of thing is “strength”? We interviewed him.

The ‘strength’ that I am thinking of is not just about abilities, it is also a bit different from strength of spirit; it is actual performance/competition strength….. strength with regards to the environment. Humans, when they face a change in environment, anyone will be anxious, and they cannot perform as usual. Any sports would be like that. Figure skate also, the competition is not in the same environment as the practice. The person who can perform as desired is really a strong competitor. For example, one can be affected when the body feels different due to jet lag or plane movements, or by the mood of the competition or the different feel of the ice. But in the midst of all that, to be able to perform like the usual practice, to perform as desired, to fully show your abilities, that person is really a strong competitor. In that sense, I still have a long way to go. To be able to do a perfect performance without being affected by changes in the environment – I think that is the real meaning of ‘strength’.

During competition, to be under the most tension, to join it with peaking and to show fully your own abilities, I think it is necessary to become such a skater. In any case, that is what I want to aim for.

The reason why I admire/ look up to Plushenko is in there. I have watched him since I was little. When he jumps, even if he leans forward at times, he never falls, he does not make mistakes. I have almost never seen him fail in competition. HE is the undisputed champion. I want to be like Plushenko; no matter what competition, to show fully my own abilities without being shaken, I want to aim to become such a skater.

In various environments, the rink for example, the feel of the ice (or texture or quality of the ice) is different. In those conditions, when I jump, how do I get into the feel of the jump, all this becomes experience. In the end, it is my own feeling, it is not something that someone can teach me, it is whether I can believe in myself or not. That moment before a jump, if you focus and believe 'I can do it’, then you will definitely be able to jump, there is such a thing for sure.

I like listening to interviews of various athletes and coaches. They all have their own theories… a certain “thing that one can believe in”. I think my own “thing that I can believe in” will change depending on changes in my mental state and physical condition. But how to respond flexibly to those changes, hereafter how much will I make into experience the “thing I can believe in”, I think that is the work I have to do.

translated by yuzusorbet.tumblr. Source: P&G myrepi.com

For previous translations of YUZU DAYS: here

Last season, Hanyu scored above 300 points in consecutive wins at NHK Trophy and GPF, and his GPF score was registered in the Guinness World Records. This season, he makes further evolution with the 1st successful quad loop in history and challenging 4 types of quads [t/n. should be 4 quads and 3 types] in his free programme. With a 4th straight GPF win which was a first in history, he prepares for World Championships coming up in March [t/n. and also 4CC coming in mid-Feb]. To Hanyu who continues to evolve, what kind of thing is “strength”? We interviewed him.

The ‘strength’ that I am thinking of is not just about abilities, it is also a bit different from strength of spirit; it is actual performance/competition strength….. strength with regards to the environment. Humans, when they face a change in environment, anyone will be anxious, and they cannot perform as usual. Any sports would be like that. Figure skate also, the competition is not in the same environment as the practice. The person who can perform as desired is really a strong competitor. For example, one can be affected when the body feels different due to jet lag or plane movements, or by the mood of the competition or the different feel of the ice. But in the midst of all that, to be able to perform like the usual practice, to perform as desired, to fully show your abilities, that person is really a strong competitor. In that sense, I still have a long way to go. To be able to do a perfect performance without being affected by changes in the environment – I think that is the real meaning of ‘strength’.

During competition, to be under the most tension, to join it with peaking and to show fully your own abilities, I think it is necessary to become such a skater. In any case, that is what I want to aim for.

The reason why I admire/ look up to Plushenko is in there. I have watched him since I was little. When he jumps, even if he leans forward at times, he never falls, he does not make mistakes. I have almost never seen him fail in competition. HE is the undisputed champion. I want to be like Plushenko; no matter what competition, to show fully my own abilities without being shaken, I want to aim to become such a skater.

In various environments, the rink for example, the feel of the ice (or texture or quality of the ice) is different. In those conditions, when I jump, how do I get into the feel of the jump, all this becomes experience. In the end, it is my own feeling, it is not something that someone can teach me, it is whether I can believe in myself or not. That moment before a jump, if you focus and believe 'I can do it’, then you will definitely be able to jump, there is such a thing for sure.

I like listening to interviews of various athletes and coaches. They all have their own theories… a certain “thing that one can believe in”. I think my own “thing that I can believe in” will change depending on changes in my mental state and physical condition. But how to respond flexibly to those changes, hereafter how much will I make into experience the “thing I can believe in”, I think that is the work I have to do.

translated by yuzusorbet.tumblr. Source: P&G myrepi.com

For previous translations of YUZU DAYS: here

Marcadores:

2017,

entrevista,

P&G,

Patinação,

Yuzuru Hanyu

quinta-feira, 2 de fevereiro de 2017

FOUR CONTINENTS CHAMPIONSHIPS 2017 (Schedule)

|

| hanyuzu94.tumblr |

LOCATION: South Korea

SCHEDULE OF EVENTS

Date /Time/ Event

Tuesday, February 14 / All day / Official Practice

Tuesday, February 14 / 10:00 / PAIRS - Technical Panel Meeting

Tuesday, February 14 / 11:00 / Team Leaders Meeting

Tuesday, February 14 / 12:15 ICE DANCE - Technical Panel Meeting

Tuesday, February 14 / 18:10 LADIES - Technical Panel Meeting

Wednesday, February 15 / All day / Official Practice

Wednesday, February 15 / 08:30 / Referee & Technical Controllers Meeting

Wednesday, February 15 / 09:30 / ICE DANCE - Initial Judges Meeting

Wednesday, February 15 / 11:30 / PAIRS - Initial Judges Meeting

Wednesday, February 15 / 12:10 / MEN - Technical Panel Meeting

Wednesday, February 15 / 17:00 / LADIES - Initial Judges Meeting

Wednesday, February 15/ 20:00 / ISU and Judges Dinner

Thursday, February 16/ 09:00 / MEN - Initial Judges Meeting

Thursday, February 16 / /11:00 / ICE DANCE - Short Dance

Thursday, February 16 / 14:15 / PAIRS - Short Program

Thursday, February 16 / 17:00 / Opening Ceremony on Ice

Thursday, February 16 / 17:50 / LADIES - Short Program

Friday, February 17 / 13:30 / ICE DANCE - Free Dance

Friday, February 17 / 17:45 / MEN - Short Program

Friday, February 17 / 18:00 / ICE DANCE – Technical Panel Review Meeting

Saturday, February 18 / 09:00 / ICE DANCE – Judges Round Table Discussion

Saturday, February 18 / 14:00 / PAIRS – Free Skating

Saturday, February 18 / 18:00 / LADIES – Free Skating

Saturday, February 18 / 18:15 / PAIRS – Technical Panel Review Meeting

Sunday, February 19 / 07:00 / PAIRS – Judges Round Table Discussion

Sunday, February 19 / 07:45 / LADIES – Technical Panel Review Meeting

Sunday, February 19 / 09:00 / LADIES – Judges Round Table Discussion

Sunday, February 19 / 11:00 / MEN – Free Skating

Sunday, February 19 / 16:30 / MEN – Technical Panel Review Meeting

Sunday, February 19 / 17:30 / EXHIBITION

Sunday, February 19 / 17:45 / MEN - Judges Round Table Discussion

Sunday, February 19 / 21:00 Closing Banquet

Please note: This schedule is subject to change.

Marcadores:

2017,

Patinação,

Yuzuru Hanyu

RISE OF THE JAPANESE POWERHOUSE

By Akiko Tamura

Source: ifsmagazine

The competitive figure skating spirit that we see today in Japan is the result of a carefully planned and well-executed program that was set in place more than two decades ago.

Many wonder how it has become such a strong nation in recent years, producing one champion after another. There is no one simple answer, but the result is a combination of various factors that have contributed to that nation’s rise on the global stages.

Figure skating has a long history in Japan dating back to the late 1920s in the men’s field and the mid-1930s in the ladies’ discipline.

The Japanese Skating Federation (JSF) was founded in 1929. Kazuyoshi Oimatsu, the federation’s first Olympic representative, placed ninth at the 1932 Olympic Winter Games in Lake Placid, N.Y.

Etsuko Inada, who won seven national titles, was the first lady to represent Japan at the Winter Games. In 1936, at age 12, she placed 10th in of a field of 23.

One of the first skaters to represent Japan in the modern era was Nobuo Satō, who dominated the sport domestically for a decade, winning 10 consecutive national titles from 1957 to 1966. It is a record that has not been broken to this day.

Satō’s fourth-place finish at the 1965 World Championships marked Japan’s highest result at the global competition. He was invited to go on tour with the medalists, but had to leave before it completed its run to compete at the national championships. “When I was competing it was a different era,” Satō recalled.

“That was a time everyone believed that if you are a student, school has to come first. So Japanese nationals were held during the spring break in March.”

Satō, the father of 1994 World champion Yuka Sato and the current coach of Mao Asada, retired following a fifth-place finish at 1966 Worlds and turned to coaching. Kumiko Okawa, his first student, placed fifth at the 1967 and 1968 World Championships. Satō later married Okawa, who is also a well-respected coach in her own right.

Tsuguhiko Kozuka, a three-time national champion, and his son, Takahiko Kozuka, the 2011 World silver medalist, were both coached by Satō.

Minoru Sano captured the first World medal, a bronze, at the first World Championships that Japan hosted in Tokyo in 1977. Shoichiro Tsuzuki, one of Yuzuru Hanyu’s first coaches, was Sano’s main coach; Satō worked with him on compulsory figures. “We had three strong men at the time: Sano, Fumio Igarashi (a two-time NHK Trophy champion and fourth at 1981 Worlds), and Mitsuru Matsumura (sixth at the 1980 World Championships),” Satō recalled. “The three of them challenged each other and the rivalry helped all of them to become better skaters. Rivalry was always the key.”

Emi Watanabe was the first lady to medal at a World Championships, capturing the bronze in 1979. Born to a Filipino mother and Japanese father, Watanabe was fluent in both Japanese and English. Her coach, Etsuko Inada, recommended that she to go to the U.S. to train, a move that was considered highly unusual at the time. At age 10, Watanabe relocated to the U.S. to work with Felix Kaspar, and later with Carlo Fassi.

Unlike today, it was rare in that era for Japanese skaters to train abroad, due to the language barrier and the financial considerations. Those factors made Watanabe’s successful path a hard act to follow. Watanabe became Japan’s sweetheart following those World Championships and “Emi” was the most popular first name for baby girls born that year. Then came Midori Ito, who completely revolutionized ladies figure skating in Japan.

CHANGING PERSPECTIVE

Machiko Yamada, who competed in the 1960s, recalled how different figure skating was during her era than it is today. “I did not enjoy skating because my coaches were very strict and I was afraid of them. That was the generation — everyone was pretty much like that at the time.”

Yamada could not wait to quit competing and when she did, she turned to coaching. Decades later Yamada, now 73, still works out of the same rink in Nagoya where she coached Ito to international glory so many years ago. Looking back on her own career, Yamada said she realized that if she had enjoyed skating more, she probably would have done better. “When I started coaching, it wasn’t like I had a big ambition, but I decided that I would make sure my students enjoyed skating.”

She remembers the day she first spotted a tiny 5-year-old Ito skating tirelessly around the rink. “It wasn’t like, ‘Wow, she has talent!’” Yamada recalled. “I noticed her because she was enjoying skating so much — she never wanted to stop.”

Shortly after joining Yamada’s class, Ito’s talent became apparent to everyone. Ito mastered four different triple jumps while she was still in elementary school. Yamada said she was fearless as a child. When Ito’s parents separated and her family situation became complicated, she began spending more time at Yamada’s home, moving in permanently at age 10. Yamada said her initial goal was for Ito to be able to financially support herself in the future through her skating.

Yamada ended up guiding Ito to so much more than that initial objective, taking her to nine national titles, the 1989 World crown and Olympic silver in 1992.

Before Ito, Tokyo had been the center of the skating universe in Japan and those who trained outside the capital had to prove that they could skate. Ito’s success put Nagoya on the national figure skating map. At the time, the JSF was constantly looking for role models outside of Japan, a practice with which Yamada did not agree. “Back then, we always looked up to the top Western skaters and tried to copy them,” Yamada recalled. “But I felt that as long as we were copying somebody, we would never become number one.”

Ito then started working on the triple Axel, a jump no woman had ever landed, and at the 1988 NHK Trophy she cleanly executed the first triple Axel in international competition. The following year, Ito became the first Asian to ever win a World title. The little girl from Nagoya had become a global skating sensation.

Though she was the favorite heading into the 1992 Winter Olympic Games in Albertville, Ito ultimately placed second behind America’s Kristi Yamaguchi. But Ito’s personal story and her Olympic success ignited a new generation of girls to take up figure skating and the sport started to gain popularity in Japan.

A NATION ON THE RISE

Without doubt, Ito was the catalyst for the generations that followed, and it was through her that the JSF gained a lot of valuable knowledge. “We learned that having just one talented skater was not good enough. We needed to build a strong team,” said Noriko Shirota, then the assistant director of JSF. (In 1994, she became the JSF director, a position she held for 12 years).

In 1992, Shirota and the JSF staff established a Youth Development Summer Camp, with the initial objective of finding and developing young talent to prepare for the 1998 Olympic Winter Games in Nagano. In the first year, about 100 skaters between the ages 8 and 12 were selected from all parts of Japan to attend the camp.

While they were being tested for their skating abilities, the youngsters had the opportunity to meet their rivals and witness first-hand what others were capable of, with the hope that this would help cultivate their competitive spirit.

The JSF then began sending novice skaters to international competitions so that they could gain experience from an early age. That program continues today and has become an important foundation for building a continuous roster of talented young skaters.

While one generation is competing at the elite level on the international stages, the next is being groomed. Fumie Suguri, Daisuke Takahashi, Miki Ando, Mao Asada and Yuzuru Hanyu were among those who were discovered at the development camps over the ensuing years.

One of the biggest discoveries at the inaugural camp was Shizuka Arakawa. Six years later, the then 16-year-old represented Japan at the 1998 Games, where she finished 13th overall. “When I competed in Nagano, I didn’t fully understand the meaning of being at the Olympics. I just thought I was lucky,” Arakawa recalled.

In 2004, she won the World title in Dortmund, Germany. Everyone was surprised, including Arakawa. “I thought that if I skated clean, I may have a chance for a medal, but I never thought of winning the gold,” she said. “My goal was to show the best performance before I retired, and I thought it was a nice finale to my competitive skating career.”

Though she was ready to move on, those around her were questioning her timing. The next Olympics were two seasons away so why quit now, they asked. Over time, Arakawa rethought her earlier decision, adjusted her plan and began to focus on the 2006 Olympic goal. “In Nagano, I was happy just to be there, but I decided that if I was to go to Torino, I’m there to compete,” she recalled.

The investment by the JSF started to pay off during the 2003-2004 season when the Japanese ladies swept the elite international podiums. Miki Ando won the World Junior and Junior Grand Prix Final titles; Fumie Suguri claimed gold at the senior Grand Prix Final; Arakawa won the World title and Yukina Ohta captured the Four Continents crown.

Things did not go quite as well the following season, but the seeds had been sewn and a new sense of rivalry had developed. The ladies team for the 2006 Olympic Winter Games was selected after a fierce national battle between Suguri, Arakawa, Ando, Yoshie Onda and Yukari Nakano. Asada placed second at those nationals but was ineligible to compete at the upcoming Games due to her age.

Three ladies were selected: Ando, 18, was the only lady to have landed a quadruple jump (a Salchow); Suguri, 25, was a two-time World bronze medalist, and Arakawa, 23, the 2004 World champion. Each one had a reasonable chance to win a medal, so none of them had to bear the pressure alone.

In the end, it was Arakawa who skated into history when she won the 2006 Olympic title, the first athlete from Asia to ever mine Olympic gold in the sport of figure skating. It was the only medal Japan won at those Games.

She became an overnight superstar, and 14 years after the Ito era, Arakawa’s victory created yet another huge wave of figure skating fever. Shirota said the difference between Albertville and Torino was that Japan had made the investment to develop a team that was highly competitive. As she had said after the Games in Albertville, Japan needed to build a strong team and it had successfully done so, especially in the ladies’ discipline. Osamu Kato, the official trainer for JSF, remembered watching Ando and Asada at the Youth Development Summer Camp years earlier.

“Their exceptional physical abilities were so apparent,” he said. “Especially Mao, who had spring like nobody else — even on the floor she was hopping and skipping when everyone else was just walking.”

Asada’s talent was closely monitored from the outset. An admirer of Ito, Asada had landed a triple Axel-double toe loop combination at a local competition when she was 13. While still in sixth grade, she was invited to compete at Japanese nationals, where she landed a triple flip-triple loop-triple toe loop combination.

“I wish I could have preserved her in a time capsule,” Shirota lamented.

Yamada, who was Asada’s coach at that time, deflects any credit for her student’s jumping abilities. “I know people say I’m a good jump coach, but it was totally by accident that good jumpers came to me,” said Yamada, who also trained Onda and Nakano, both of whom were considered solid jumpers. “Personally, I always preferred expressive skaters. When I saw the Asada sisters I was thrilled and thought that they could be all-round skaters.”

Asada left Yamada after six years and relocated to the U.S. to train with Rafael Arutyunyan. She subsequently moved to work with Russia’s Tatiana Tarasova in the lead-up to the 2010 Olympic Winter Games.

The first Japanese skater to win three World titles, Asada found success at any early age and her continued rise on the international stages over the following decade spawned more waves of figure skating enthusiasm in Japan.

Asada’s triple Axel legacy has flowed down to the next generation. At the Junior Grand Prix event in Slovenia this September, 13-year-old Rika Kihira successfully landed a triple Axel on her way to winning the competition, defeating her teammate and current World Junior champion Marin Honda.

“Rivalry seems to be always the key to reaching the next level,” Satō said.

THE MEN STEP UP

Unlike the ladies, there was a long pause between Sano’s accomplishment at the World Championships and the next Japanese man to become an international star. Takeshi Honda, who at age 14 became the youngest man to ever win the national title, went on to claim two consecutive World bronze medals in 2002 and 2003.

When Honda retired in 2006, another star was waiting in the wings. Daisuke Takahashi found success at age 15 when he claimed Japan’s first World junior title in 2002.

Though he struggled in subsequent years to reach the podiums at senior competitions, it all came together one night on Olympic ice in Vancouver in 2010. There, Takahashi wrote his own piece of history when he claimed bronze, and became the first Japanese man to medal at an Olympic Winter Games in figure skating. A month later he won the World title, another first not just for Japan, but also for Asia.

“I always envied that it was the ladies that got all the attention. I was hoping to bring some of the spotlight onto the men as well,” Takahashi said.

His achievements marked a turning point for men’s figure skating in Japan. Just as he had hoped, more attention was focused on the male skaters. Fans started attending competitions in droves and the media began to take the sport seriously.

Nobunari Oda, another big star to come out of Japan, won the 2005 World Junior Championships, and in his senior debut later that year, claimed medals at both of his Grand Prix assignments.

Kozuka was the next member to join the club following his victory at the 2006 World Junior Championships. When he joined Takahashi and Oda in the senior ranks the following season, Japan had a trio of men vying for the top spot at the national championships. This three-way rivalry raised the bar domestically and turned nationals into a heated affair. All three captured the title at one time or another during a seven-year period.

The competition became especially fierce when a young man from Sendai joined the battle in the fall of 2010. Hanyu, the 2009 Junior Grand Prix Final and 2010 World Junior champion, adored Takahashi, but that did not stop him from claiming the national crown in 2012. Hanyu successfully defended his title the following season and entered the 2014 Olympic Winter Games as the reigning national champion and Japan’s best hope for a medal in Sochi.

To everyone’s surprise, Hanyu waltzed off with the gold medal, becoming the first Asian man to win an Olympic figure skating title. He has, in his few short years on the international circuit, set the bar technically and made history repeatedly. He holds the record for the highest score ever awarded under the current judging system, which he earned at the 2015 Grand Prix Final. Although his score of 330.43 seems untouchable — at least for now — Hanyu shows no sign of slowing down.

He opened the 2016-2017 season with another historical feat, successfully landing the first ratified quad loop at the Skate Canada Autumn Classic in Montreal in September. “I achieved what I achieved last season. It is natural for me to move forward and try something new,” said Hanyu, 21.

Shoma Uno, his 18-year-old homeland rival, successfully executed a quad flip at the Team Challenge Cup last April. He is the only skater to have landed this jump in competition to date.

Japanese figure skating has come a long way since Sano won Japan’s first World medal almost 40 years ago. In the past decade, Japanese skaters have claimed seven World titles and 12 other medals of varying colors; two Olympic crowns, as well as two silvers and a bronze, and have won five World Junior titles.

Every nation has its highs and lows, but the development of the Japanese skating program has seen it rise from being a nation of hit and miss wins to one of the strongest in the world.

Behind the scenes, there is a wealth of talent coming up through the ranks, and the nation seems virtually guaranteed to continue the success it has enjoyed throughout the past 15 years.

Originally published in the November/December 2016 issue of International Figure Skating magazine.

Acho esse artigo esclarecedor, nele temos o vislumbre de todo o travalho que foi feito no Japão para se tornar uma potencia mundial da patinação artistica.

Talentos como Yuzuru Hanyu precisam ser encontrados, trabalhado e apoiados para que possam se desenvolver e nos maravilhar com seu talento.

Parabéns a todos os países que apoiam e trabalham seus talentos!

A tradução desse artigo para o português está aqui.

Marcadores:

2016,

2017,

News,

Patinação,

Yuzuru Hanyu

Pages

Favorites Links

Visualization

About me

Jo de Souza

22/04/2015

Popular Post

Blog Archive

Labels

Yuzuru Hanyu

Patinação

2015

2016

Seimei

2017

entrevista

Chopin

Canadá

News

Campanha

Fantasy on Ice

P&G

Grand Prix

GALA

Hope&Legacy

Let’s Go Crazy

Olimpíada

2014

NHK Trophy

Requiem

World Championships

Javier Fernandez

Brian Orser

Sendai

Videos

Kobe

Lotte Ghana

Mundial

Parisienne Walkways

Romeu e Julieta

Kanazawa

2013

24HTV

Believe

premium talk

Dreams on Ice

Japanese Nationals

LIvros

Sochi

World Team Trophy

4CC

Cruz Vermelha

Kenji's Room

White Legend

2011

2012

2018

Hana ni Nare

Hello I love You

Nagaoka

Phiten

Shoma

Shows

Vertigo

Étude op 8 no. 12

2010

E-earphone

Nobu

Photos

Programas

Toronto

2009

66º Kouhaku Utagassen

Ano Novo

Curiosidades

Fanart

Filme

Prince Ice World

Skating Shows

Tanabata

2009 - Yuzuru Hanyu BR. Powered by Blogger

Blogger Templates created by Deluxe Templates

Wordpress Themes developed by Templatelite.com

Blogger Templates created by Deluxe Templates

Wordpress Themes developed by Templatelite.com